Hardware Architecture

Introduction

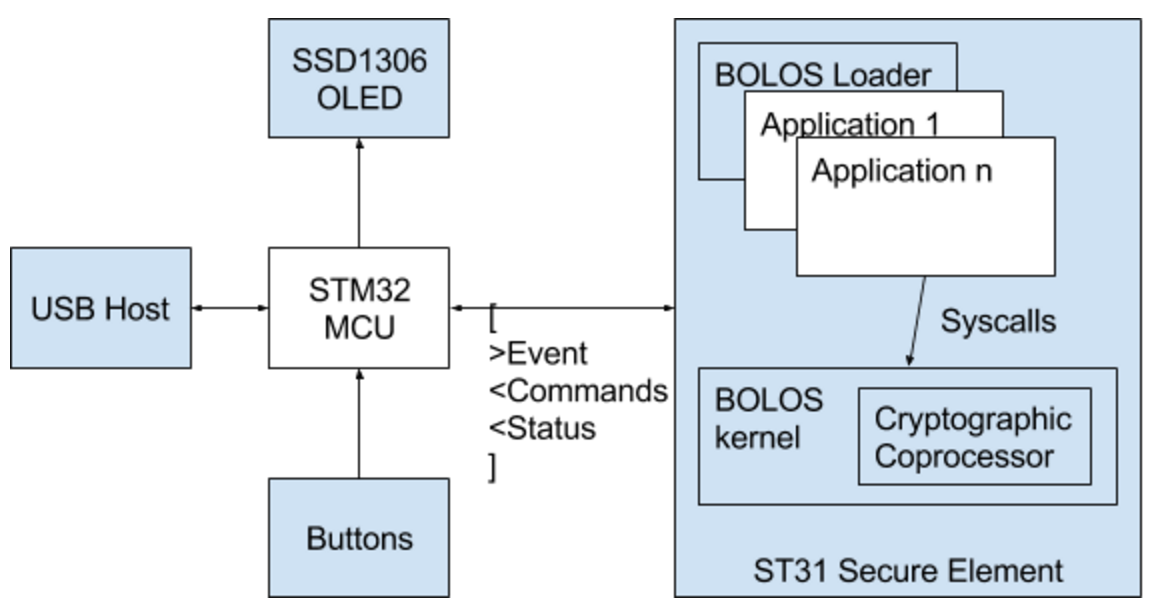

Ledger devices have a very unique architecture in order to leverage the security of the Secure Element while still being able to interface with many different peripherals such as the screen, buttons, the host computer over USB, or Bluetooth & NFC in the case of the Ledger Blue.

In order to accomplish this, we attached an additional STM32 microcontroller (the MCU) to the Secure Element (the SE) which acts as a “dumb router” between the Secure Element and the peripherals. The microcontroller doesn’t perform any application logic and it doesn’t store any of the cryptographic secrets used by Ledger OS, it simply manages the peripherals and notifies the Secure Element whenever new data is ready to be received. Ledger OS applications are executed entirely on the Secure Element. In this section, we’ll take a look at the hardware architecture to better embrace the hardware related constraints before analyzing their software implications.

Multiple Processors: Secure Element Proxy

A detailed Ledger OS architecture diagram

A detailed Ledger OS architecture diagram

Ledger OS is split between two hardware chips, one being secure, and the other having JTAG enabled and acting as a proxy.

| Hardware signer | Microcontroller (MCU) | Secure Element (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Ledger Nano X | STM32WB55 / STM32WB35 | ST33J2M0 |

| Ledger Nano S Plus | STM32F042 | ST33K1M5C |

| Ledger Stax | STM32WB35 | ST33K1M5C |

| Ledger Flex | STM32WB35 | ST33K1M5C |

Furthermore, the Secure Element is also split into two parts: the firmware which is under NDA and is therefore closed-source, and the SDK & application-loaded code which is open source friendly. The Ledger OS firmware is responsible for low-level I/O operations and implements the SE-MCU link (though the handling of the protocol between the SE and the MCU is done by the currently running app).

Ledger OS relies on the collaboration of both chips to empower Secure Element applications. At first glance, and even at second and all following, the Secure Element is a very powerful piece of hardware but lacks inputs / outputs. In our architecture, we solved this problem by appending the MCU which is full of inputs / outputs so it can act as a proxy for the Secure Element to explore new horizons. In a sense, the MCU can be seen as a supercharged coprocessor of the Secure Element. Not considering security implications (which is beyond the scope of this section), and thanks to a simple asynchronous protocol, the Secure Element drives the proxy.

The SE-MCU link protocol is called SEPROXYHAL or SEPH in source code and documentation. The “HAL” stands for Hardware Abstraction Layer.

SEPROXYHAL

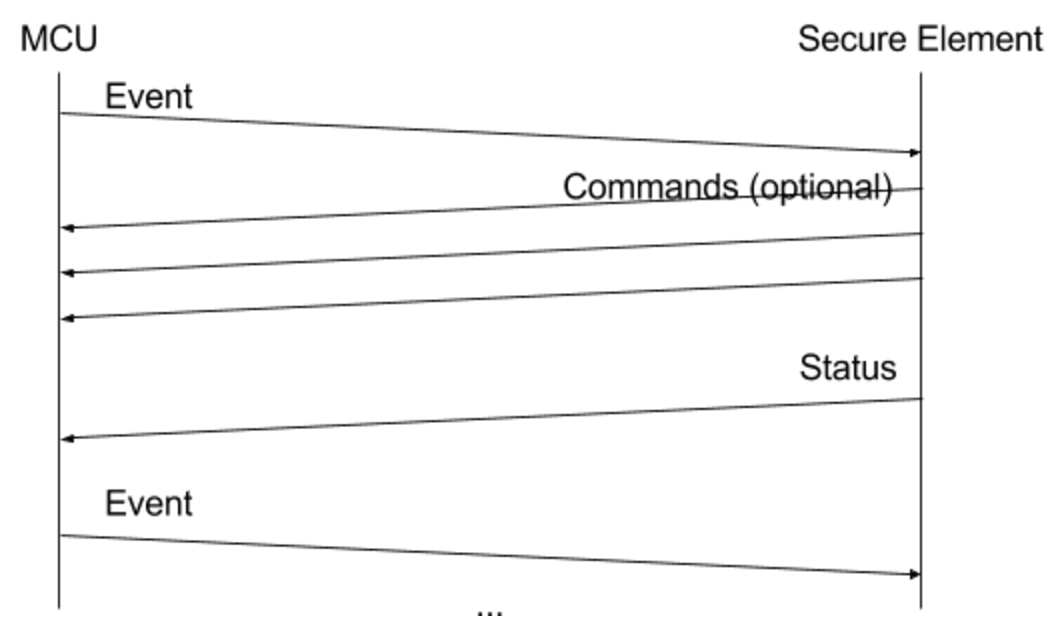

The SEPROXYHAL protocol is structured as a serialized list of three types of packets: Events, Commands, and Statuses. Since SEPROXYHAL is the only channel for the SE to communicate with the outside world, if there is an error at the protocol level (such as the order or formatting of Events / Commands / Statuses getting messed up), then the SE ends up completely isolated and unable to communicate. When developing an application this is typically the most common failure scenario. If this happens, the device must be rebooted to reset the SEPROXYHAL protocol state. Hopefully, multiple levels of software guards are implemented to avoid such cases.

The protocol works as follows:

- The MCU sends an Event (button press, ticker, USB transfer, …).

- The SE responds with a list of zero or more Commands in response to the Event.

- The SE sends a Status indicating that the Event is fully processed and waits for another Event.

SEPROXYHAL protocol concept

SEPROXYHAL protocol concept

As a matter of fact, due to buffer size, requests to display something to the screen are sent using a Status. When the MCU has finished processing the Display Status, it issues a Display Processed Event indicating that it is ready to receive another Display Status. As a result, displaying multiple elements on the screen (in order to build an entire user interface) must be done asynchronously from the core application logic. This process is facilitated by a UX helper implemented in the SDK, which will be discussed further in the next chapter.

The SE throws an exception to applications willing to send more than one Status in a row, without a new Event being fetched in between.